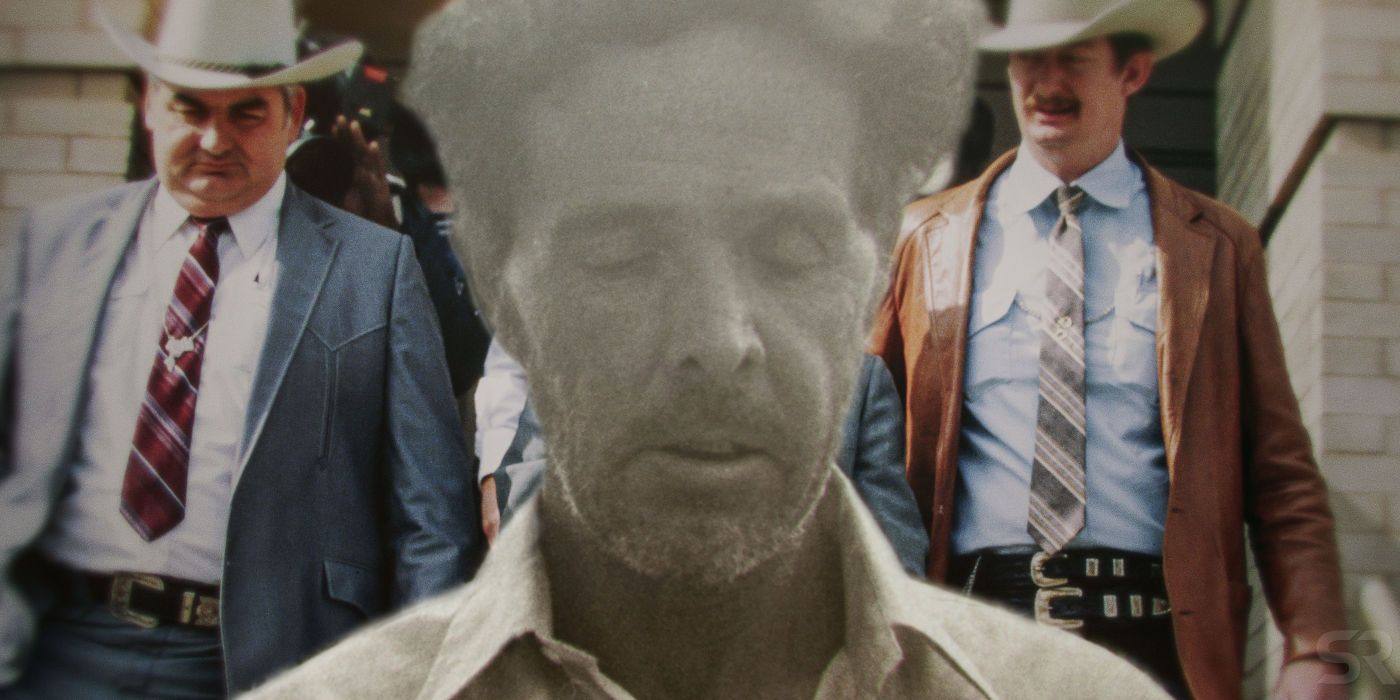

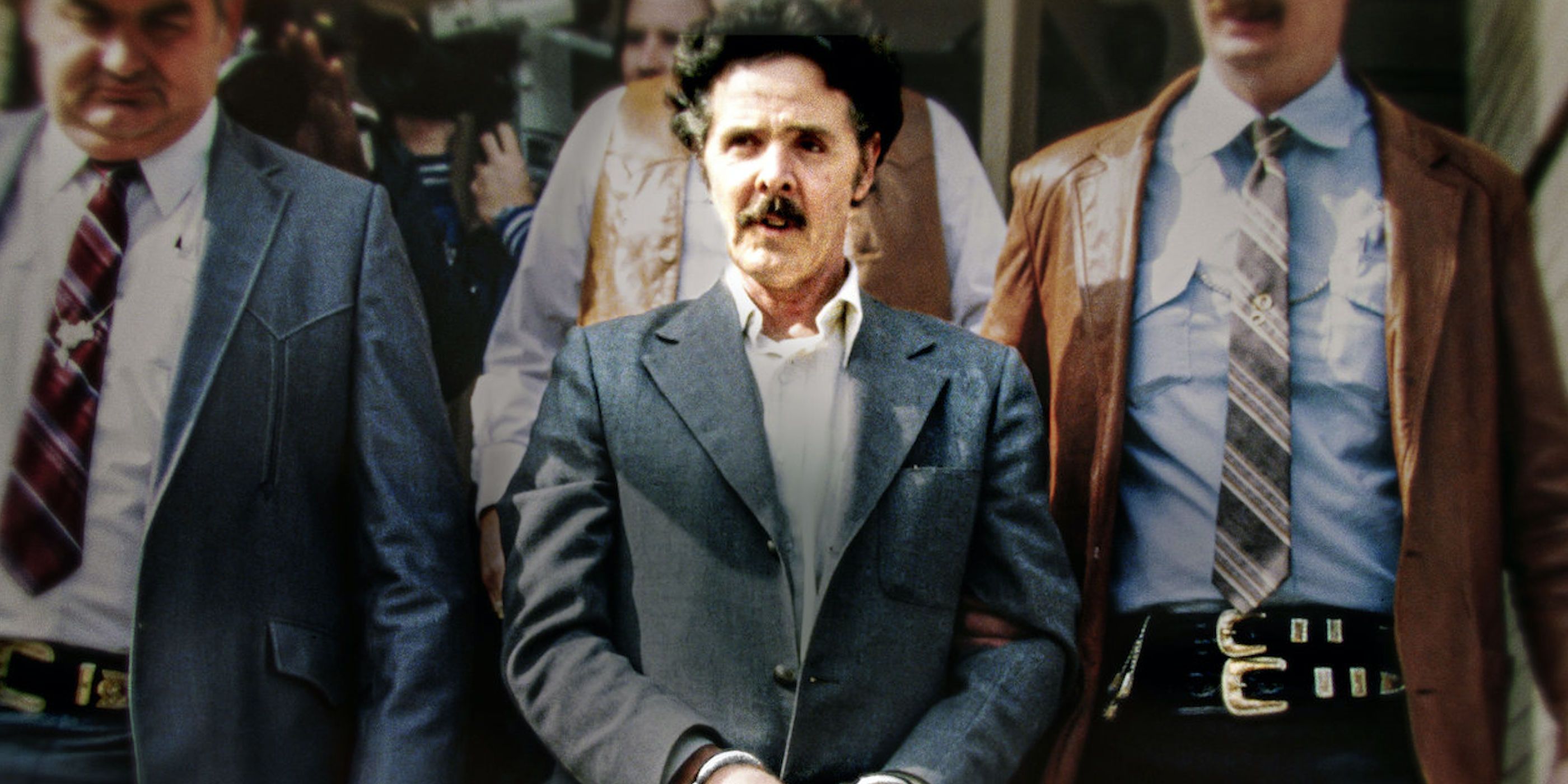

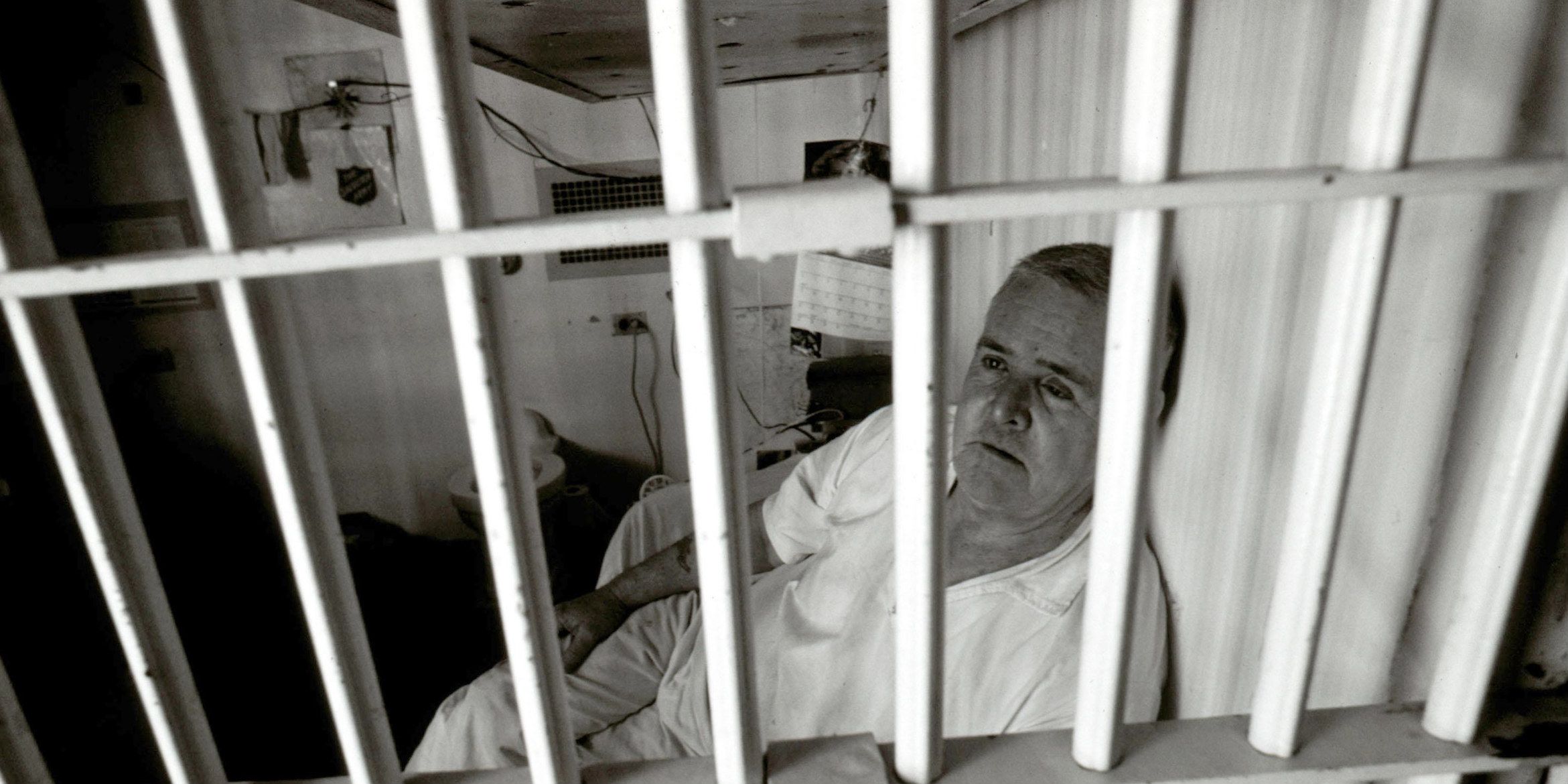

The Confession Killer includes many disturbing revelations about alleged serial killer Henry Lee Lucas, most notably that he didn’t actually commit hundreds of murders during the '70s and '80s. Directed by Robert Kenner and Taki Oldham, the five-part Netflix docuseries explores how a troubled man was manipulated by both the legal system and his own mind.

In 1960, Lucas murdered his mother and spent the decade in jail. In the '80s, he admitted to killing two more women and was questioned by Texas Rangers. Lucas ultimately confessed to killing more than 600 people, and became known as the most prolific serial killer in American history. But authorities (and the family members of victims) ultimately realized that Lucas' claims didn’t match the evidence. When he passed away from natural causes in 2001, many of his confessions had been discredited by journalists.

The Confession Killer suggests that Lucas lied not to orchestrate a grand conspiracy, but to please those who took care of him, and because a complex psychological disorder affected his interpretation of memories. Here are The Confession Killer’s biggest reveals about Lucas, a man who looked for attention in all the wrong places.

Lucas began confessing to unsolved murders in 1983. By that time, the trial and conviction of serial killer Ted Bundy had forever changed the dynamics of American news coverage. Lucas became the new media sensation, so journalist Hugh Aynesworth decided to meet the alleged killer after spending four years interviewing Bundy for the books The Only Living Witness and Conversations with a Killer, the latter of which inspired the 2019 Netflix docuseries of the same name.

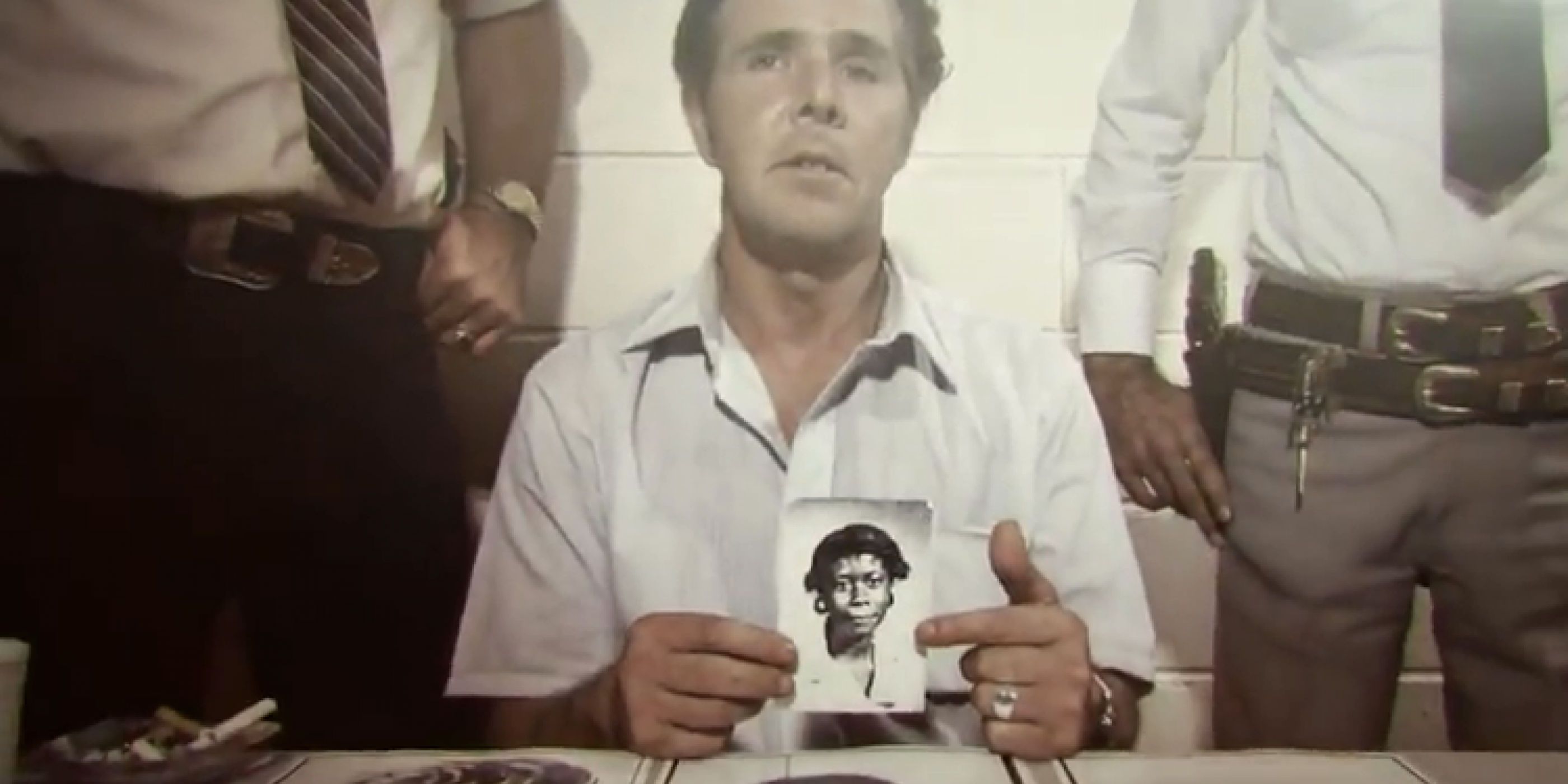

According to Aynesworth, he was free to visit with Lucas “any day of the week, any time of the day.” But whereas Bundy was known for his intelligence and law background, Aynesworth realized that Lucas was "just a dirtball." The Bundy investigator then assembled a Japanese film crew (much to the delight of Sheriff Jim Boutwell), and Lucas can been seen grinning on camera while discovering that he’s famous in Japan, and even claims to have killed people there. Not only that, but Lucas states that he’d driven his car to Japan - an obvious lie that’s seemingly meant to impress the Japanese journalists. In that moment, Aynesworth realized that Lucas could tell a good story, but the man's lack of intelligence - and willingness to please the present crowd - was immediately apparent. The Confession Killer shows how Texas Rangers managed to use Lucas’ vulnerabilities to their advantage and "solve" hundreds of murders.

In The Confession Killer on Netflix, Lucas states on camera that his dark impulses increased when he met fellow killer Ottis Toole. The duo had a sexual relationship (which retired Texas Ranger Bob Prince briefly mentions in The Confession Killer), one that resulted in both men trying to impress each other (and authorities) with tall tales about their criminal past. Lucas' need to please and impress Toole directly precedes his need to please and impress Texas Rangers with fictional stories about various murders.

In 1983, Toole claimed to have murdered six-year-old Adam Walsh; the son of John Walsh, who would later host the groundbreaking TV series America’s Most Wanted. The confessions of both Toole and Lucas earned them attention from law enforcement officials, but also overshadowed the truth. In reality, both men did kill - just not as much as they claimed. In 2008, Florida authorities announced that Toole had most likely killed Adam Walsh; a murder that Lucas once claimed to have been associated with. According to The Confession Killer, Toole wanted to “match whatever Henry said”; their conversations were “exaggerated boasting.” The Lucas-Toole relationship is a mix of dark truths and pure fiction.

Lucas created a myth about his American drifting, one that was perpetuated by Texas Rangers who closed murder cases based on flimsy evidence. In The Confession Killer, one particular sequence shows how Lucas would have needed to travel back and forth across America - at 50 miles per hour, and with no breaks - in order to commit various murders.

During a one-month stretch, according to the official timeline, Lucas committed a murder in Washington, drove 2,000 miles for an attempted abduction in south Texas, drove another 600 miles north for a murder in Arkansas, and then traveled 950 miles west to kill someone in New Mexico. Shortly after, Lucas allegedly drove another 1,000 miles for a murder in Nevada, and then drove another 1,600 miles to Louisiana, only to travel 2,100 miles back to Washington for a murder two days later, just before another 2,000 mile journey to kill once again in Missouri. In October 1978, Lucas would have traveled 11,000 miles based on his murder confessions. Today, authorities would quickly debunk such claims. In the ‘80s, however, Texas authorities ran with the story, either because Lucas was so convincing or because it was a good look for brand management.

Vic Feazell, a former McClellan County District Attorney, nearly spent years in jail because of Lucas’ false confessions. He speaks on camera throughout The Confession Killer, and recalls his glory days during the ‘80s before he released the Lucas Report, an exposé that heavily contrasted with the Texas Rangers’ official account about Lucas' alleged crimes. Feazell details how Texas Ranger boss James B. Adams, a former FBI director, used scare tactics and the media to prevent the D.A. from damaging the organization's reputation.

Journalist Charles Duncan led a smear campaign against Feazell, evidenced by an 11-part TV series that culminated with the District Attorney’s arrest (and acquittal) for accepting bribes to influence cases. After returning to his position, Feazell resigned and dedicated his time to defending Lucas. In The Confession Killer, Feazell frequently discusses the hardships of the experience, and how it affected his personal life with both his wife and children.

Feazell ultimately separated all ties with Lucas when the killer tried to raise the dead. One of Lucas’ alleged victims, Becky Powell, was inexplicably tracked down and told a bizarre story of survival that seemed to help Feazell’s defense case. Unfortunately, the woman turned out to be one of Lucas’ admirers, Phyllis Wilcox. In written letters, Lucas had embedded various details about Powell, allowing Wilcox to piece together a story that the public would believe. In The Confession Killer, Feazell reflects about wanting to improve his reputation prior to the Wilcox fiasco, and coming to the understanding that any further association with Lucas would be a bad look: “I’d just had enough.”

The collective interviews in The Confession Killer reveal that Lucas suffered head trauma between the ages of five and 10, and had a low IQ. He also "hated" women and killed his own mother before confessing to hundreds of murders. For whatever reason, Lucas found a genuine connection with the aforementioned Toole, and the relationship allowed them to practice conversational techniques. By the early ‘80s, Lucas performed for a new audience, the Texas Rangers.

In The Confession Killer, the final episodes heavily imply that Lucas unwittingly invented new truths because of a memory disorder known as "confabulation." Meaning, he fulfilled the wants of others by creating fantastical stories based on a small set of facts. The Confession Killer shows how the hundreds of false confessions inspired better criminal profiling, and how DNA was used to identify at least 20 of the real killers. By examining Lucas' personality and case files, the FBI Behavioral Science Unit (as seen in Netflix's Mindhunter) can now better understand the motivations and psychology of both serial killers and those who have something to gain from legal proceedings.

from ScreenRant - Feed https://ift.tt/2DWvPEb

0 comments:

Post a Comment